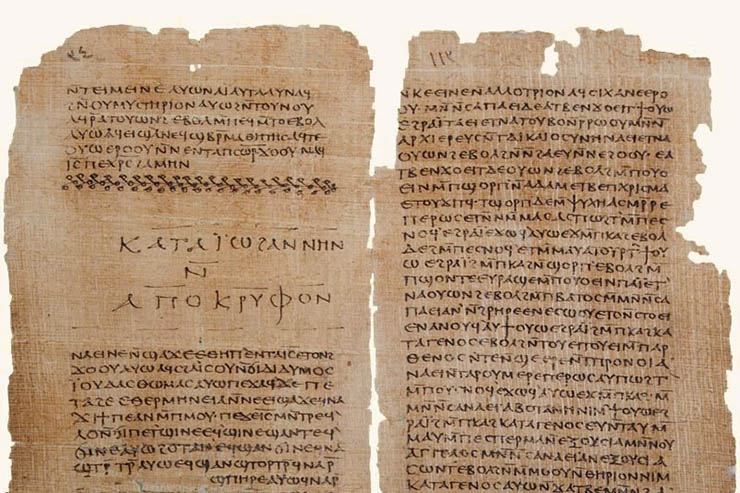

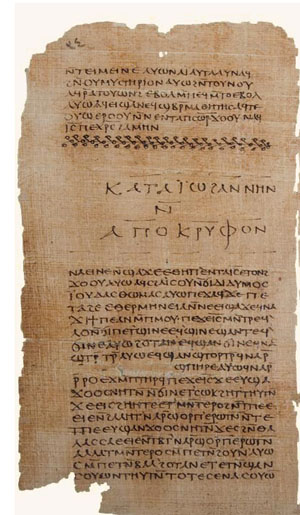

Over the last century, a number of previously lost and unknown texts have come to light and illumined the origins of the main religions of the West. The most famous include the Nag Hammadi library, unearthed in Egypt in 1945, and the Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in Israel in 1947. The Gospel of Judas is only the most recent example; in all probability it will not be the last.

What have scholars learned from these often baffling and obscure documents? The issue is a complex one, but it’s possible to sketch out a few key points.

• The historical Jesus remains a mystery. Here is a man who was revered as a divine or semidivine being very shortly after his death. And yet there is not one surviving eyewitness account of him. None of the authors of the New Testament Gospels says that he saw Jesus with his own eyes; the closest we have is Paul’s claim he saw the risen Jesus (1 Cor. 15:5–7). And with the possible exception of the Gospel of Thomas, most of the lost gospels (including the Gospel of Judas) are later than the canonical Gospels and probably do not include a great deal of true biographical details about Jesus’ life.

Some scholars have taken this fact to mean there was no such personage as Jesus, that he was a mythic figure concocted to reflect certain sacred mysteries. While this is in all likelihood too extreme a conclusion to reach, it does show Jesus remains hidden behind a cloud of mystery.

• There was not one original Christianity, but many. Some more or less resembled what would later become Catholic and Orthodox Christianity; some were Gnostics; some denied Jesus was anything more than a great teacher. These differences go so far back that they probably reflect divergences in the views of Christ’s own disciples.

• There are grounds for a hermeneutics of suspicion. Until recently, it was taken for granted that the founders of proto-orthodox Christianity were essentially correct and honest in their portrayal of Christ and his teachings. The issue is considerably more complex now. It has become obvious many of the teachings that supposedly go back to the Apostles were formulated only centuries later. The most notable is perhaps the doctrine of the Trinity, which portrays Christ as divine and fully equal with the Father. This view did not appear in early Christianity. Originally, even those who regarded Jesus in the most exalted fashion, such as the author of the Gospel of John, saw him as kind of a “second god” through whom the Father worked. This view would later be condemned as heresy. The doctrine of the Trinity was worked out by Catholic and Orthodox theologians in the fourth through sixth centuries CE.

It has been deeply unsettling to Christians to realise that many of their most cherished views may be based on myths or even misrepresentations. But it is to the credit of biblical scholars of the last 200 years that they have been willing to face these issues, even when their findings challenge the deepest core of their own beliefs.

© Copyright 2006 by New Dawn Magazine & the respective author. This article first appeared in New Dawn Special Issue 2. For further information visit http://www.newdawnmagazine.com