Ancient myths exercise such great allure that one cannot help wondering what meanings lie behind them. The great psychologist C.G. Jung suggested these myths were projections of the collective unconscious, a universal level of the mind that expresses itself in symbolic and religious forms. By contrast, the French esotericist René Guénon and his school, who believed that all the great religions are descended from a now-lost primordial tradition, held that the ancient myths were a later and muted form of this original knowledge.

To be able to sort out these claims, we would have to know how conscious the ancients were of the deeper meanings of their own myths. And the evidence is not entirely consistent. Plato, perhaps the single greatest figure in ancient philosophy, did not seem to think that they had great value. In his Republic, he even argued they should be censored so that people would not be tempted to imitate the disgraceful behaviour of the gods in so many of the tales. Other authors, as we shall see in this article, recognised that these stories were allegories pointing to higher truths.

To take a reasonably simple example, there is the story of Narcissus, the beautiful youth who fell in love with his own reflection in a pond and fell in and drowned. The most obvious – and most familiar – explanation is a psychological one. Narcissus gave his name to narcissism, an extreme and pathological fascination with oneself. But deeper explanations are possible.

In the accompanying article, I suggest that awakening human potential has to do with a growing awareness of the true “I,” the Self that is able to stand back from all of its experience and witness it clearly and objectively. Of course under ordinary circumstances we are not aware of this true “I”; otherwise we would not need to rediscover it. The myth of Narcissus suggests how it was lost. We drown in our own reflections. That is, mind, witnessing its experience, inner as well as outer, comes to identify with this experience and forgets that it is anything other. It loses its own identity and is submerged in the thoughts, feelings, and sensations of the ordinary mind.

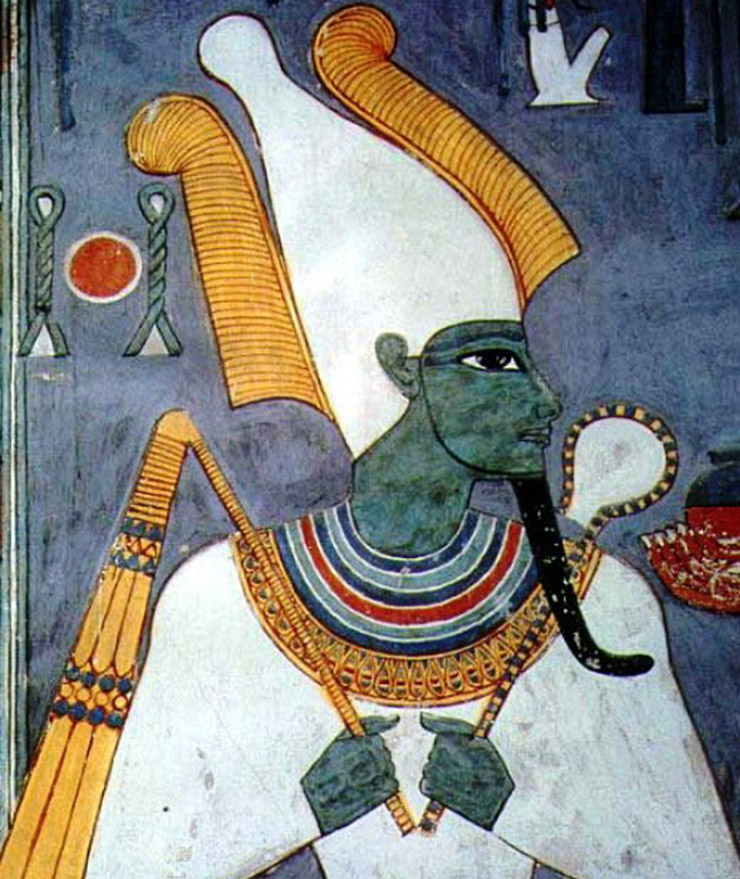

One of the most resonant of the ancient myths has a similar import. In the Egyptian myth of Isis and Osiris, Osiris was an ancient god-king who ruled beneficently over the land of Egypt alongside his sister and wife, the goddess Isis. Osiris’s brother Set became jealous of him and plotted to destroy him. Set built a magnificent cedar coffin, which he brought to a banquet that Osiris was hosting, and said that he would give the coffin to anyone who fit its dimensions. Osiris himself lay down in the coffin and his body fitted perfectly. Set had the coffin immediately closed and nailed shut, and cast it into the Nile. Isis went about in search of Osiris’s coffin and finally found it in the Phoenician city of Byblos. But when Isis was away on a trip, Set laid hands on the coffin and cut Osiris’s body into fourteen pieces, which he scattered all over Egypt. Isis again went in search of her lost husband and was able to find all the parts except for her husband’s penis. Reassembling the parts, including a simulacrum of the lost member, Isis then restored Osiris to life, and from that time on he ruled as the god of the underworld. Horus, the son of Isis and Osiris, then did battle with Set and defeated him.

We owe the most complete version of this story to Plutarch, an author of the first century CE, who wrote a treatise called On Isis and Osiris. Plutarch’s work is invaluable not only for this reason but because it offers an esoteric interpretation of the myth. Before providing his own meaning, Plutarch considers various other explanations and refutes them. Some of these explanations have an extremely modern sound, including the theory that the myth concerns “the generation of the corn and sowings and ploughings.” Plutarch calls those who believe such things a “dull crowd.”

The right interpretation, according to Plutarch, is that Osiris represents the logos, a Greek word that is usually translated as “word” or “reason” but which more accurately means the principle of consciousness that lies at the core of all beings, animate and inanimate. Isis is the feminine principle of nature, which generates all things. Set is the force of dissolution and decay. Plutarch writes, “For while the logoi and ideas and emanations of the God in heaven and stars remain [forever], those that are disseminated into things passible – in earth and sea and plants and animals – being dissolved and destroyed and buried, come to light over and over again and reappear in their births.”

Plutarch’s interpretation is cosmological. He believes the myth refers to the genesis and demise of everything in the universe. It is also possible to apply this perspective more specifically to the human condition. At the core of our being is this logos, this principle of pure consciousness, symbolised by Osiris. But in ordinary experience, consciousness does not come in a pure form; it is always consciousness of something. For humans, what we are conscious of is the whole of our experience, physical and psychological. This is symbolised by Isis: experience never ceases; like Isis, it constantly generates new forms. However, it can become fixed on a particular perspective on experience. This fixation, in contemporary terms, is called the ego. This is what Set represents. He creates a magnificent coffin, which is the physical body. Once it is entombed in this coffin, Osiris – consciousness – is immersed in the waters of obliviousness and is cut into pieces. As in the myth of Narcissus, consciousness forgets itself and identifies with its experience. This is a kind of death – but it is, paradoxically, the “death” of ordinary waking life. Only with the help of the forces of awakening, symbolised by Horus, can this dissolution be reversed.

Curiously, the only part of Osiris that is not recovered is the penis. This may be because the penis represents the generative capacity; the myth makes it clear that Osiris remains deficient in this area after his miraculous restoration. He and Isis do have another son, Harpocrates, but Harpocrates himself is weak in the lower body. This would suggest that after awakening, consciousness is no longer able to generate experience in quite the same way that it did before. The quality of the experience changes; it may be less vibrant, but there is also less attachment to it.

While this is an extremely brief version of both this myth and its interpretation, I believe it makes sense in the light of the ideas I have discussed in the accompanying article. Ordinary life, in which we think we are our experiences, is represented by Osiris’s incarceration in the coffin, for we have come to identify with the experience of the body and are symbolically dismembered along with it. But this identification is erroneous or illusory; that is, the broken fragments of consciousness can become integrated and symbolically reassembled. Consciousness then can rule in a new and glorified form.

These are universal truths. Because they are universal, this ancient myth can still speak to us. Moreover, the same motif occurs in many forms – in death and resurrection legends throughout the world, including those of Christianity. Many times they have taken the form of mysteries – sacred rites that are performed under special conditions to awaken the human potential and to remind the consciousness, the true “I” at the centre of each of us, that it must not identify with the transient and the impermanent.

Myth, as Jung stressed, often has a double meaning. On the face of it, a death-and-resurrection myth is a story designed to allay fears of death (and this, according to Cicero, was precisely the result of experiencing the ancient mysteries). On another level, the myth is saying something more and different. It does not deny life after death – quite the opposite. But it goes further; it says that what we think is waking life is a form of death, and what we think of as death is a birth to a higher life. In its esoteric forms, Christianity says much the same thing: life and death are not quite what they seem. The poet William Butler Yeats may have alluded to this truth when in his poem “Byzantium” he wrote: “I hail the superhuman. / I call it death-in-life and life-in-death.”

Of the two views of myth mentioned at the beginning of this article, I tend to sympathise more with Guénon’s than with Jung’s. I believe these myths are not, or not entirely, spontaneous eruptions from the unconscious but rather sacred teachings whose deepest meanings were always known and preserved by initiates. It was only after the traditions had perished in a living form that the myths were preserved as mere stories. Indeed we could go further and say that as soon as these deeper meanings are forgotten, the tradition perishes. One question for the future is whether these meanings have been totally forgotten by Christianity today, and whether it will collapse as a result. An alarming thought – even those who have little love for the religion may not relish the idea of being buried in the wreckage.

© Copyright 2011 by New Dawn Magazine & the respective author. This article first appeared in New Dawn No. 129. For further information visit http://www.newdawnmagazine.com